This month we have a grab-bag of observations and insights around the general theme of finding deeper principles in the things we see.

Why circumcision?

Why not a nick in the ear, for instance?

Actually, there is a circumcision of the ear for slaves (Dt 15:17)—but here are a couple of symbolic suggestions about the significance of circumcising the penis:

It is connected to the cutting of a covenant. Covenants with God are typically cut by blood (not always our blood though, and ultimately of course the blood of Jesus). This is because covenants come with curses, especially the curse of being “cut off.” Death is disintegration—the wages of sin is to be cut off from God. The baby belongs to God by covenant, and is symbolically cut in half through circumcision, to represent that the flesh that cuts him off from God has itself been cut off.

It is also connected to pruning. People are trees (hence Adam was created in an orchard; cf. Mk 8:24, Jg 9:7–21, etc). By pruning the genital organ, God is simultaneously claiming his right over it, and promising fruitfulness. Pruning is like a mini-death that leads to greater life, and this is connected to the promised seed who was given to the world through the covenant of circumcision, was planted in the earth, and rose as the first-fruits on the third day.

Btw, we are not advocating modern circumcision, which is unlike biblical circumcision, and removes a great deal more. We’re assessing the symbolism of the sacrament God gave, not the ethics of the modern practice. Don’t circumcise your babies.

Learnings from church conflicts

Having seen our share of rows, disputes, and even splits in churches, here are few takeaways about the nature of people:

Firstly, for most people, sola scriptura isn’t really a thing. Take, for instance, a church where grape juice is used in the Lord’s Supper instead of wine. If you raise the possibility that this is a wrong way to administer the sacrament, there is generally very little concern, and very little desire to examine the practice against scripture to see whether it needs to be reformed. This is not necessarily because the people don’t care about obeying God, but because they don’t primarily base their understanding of what that means on scripture itself. They base it on the established tradition of the church. Meaning-making is outsourced to the institution.

This might seem like a defect in people, but it’s not—not necessarily. As finite creatures, none of us has the capacity to examine and formulate every possible doctrine and practice by ourselves, in isolation, purely relying on our own exegetical skills. Even giants like Calvin did not. That is not how God made us. He gave the church pastors and teachers specifically to equip and build it up because no one is meet to such a challenge. And these pastors and teachers don’t lay a new foundation every generation, but build on the work already done by others, which ultimately is built on the work of the apostles and prophets (Eph 2:20-22; 4:11-17).

In other words, we are made to be members of a body, and members do what the body does.

Secondly, with that said, most people are unable to separate facts from feelings, and how they feel from who they are. Their functional authority is the body they are part of—which can be OK—but unfortunately in practice this often means their functional authority is the sentiment of the group. Even if they know that going along with the group is acting contrary to scripture, they would rather disobey God’s word than act against what they see as the group’s overall feeling.

In other words, their existential root is social rather than religious: focused on the acceptance of man, rather than the acceptance of God.

Thirdly, subsequently, most people are willing to ostracize those who threaten the status quo or harmony of the group. The corollary of this fact is that they themselves live in fear of ever threatening this harmony, lest others do the same to them.

Good church leaders should work to reform these tendencies in their congregations—i.e., they should work to sanctify their people. But they must be wise to understand the natural, creational reasons that these kinds of behaviors occur. You cannot change human nature, and you shouldn’t want to. You have to work with it. Grace restores nature—it doesn’t radically alter it or obliterate it. A good leader knows that people will always be members of a body, and they will never be atomized automatons that act according to pure logic. That would actually be worse than having a nature that is easily swayed by group dynamics.

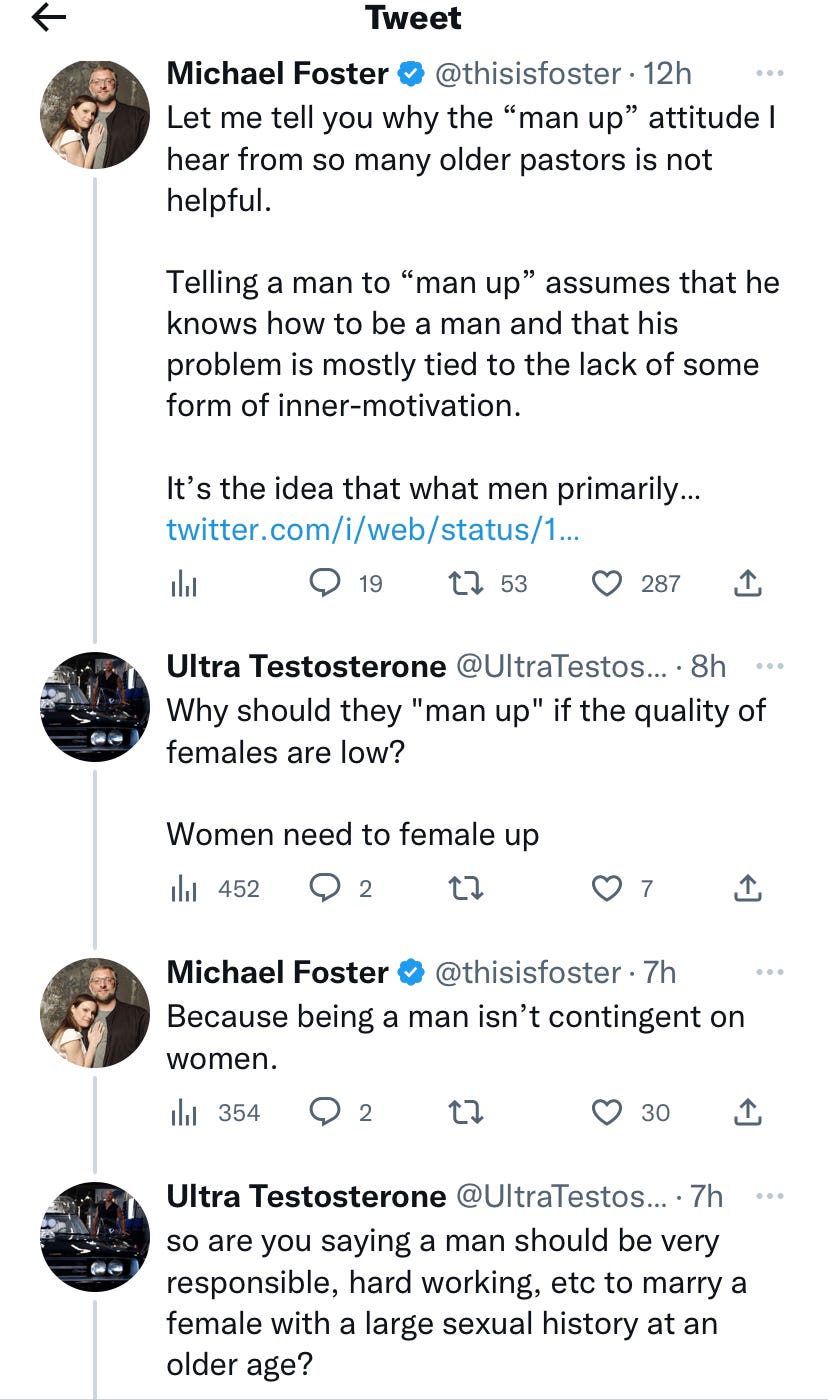

The female-centric nature of Twitter patriarchalists

A lot of young men who consume too much Twitter (sorry, X) masculinity content are given to making women the center of their world without even realizing it. Here’s an example:

False prophets encourage passivity by telling people what they want to hear

The exilic and post-exilic books of scripture are especially helpful for times like ours.

The exilic period begins with God’s judgment of Judah. Everything was destroyed—their center of worship, the temple; their means of protection; their soldiers; even the walls of Jerusalem.

All their homes and wealth were gone. It was dust, rubble, and ashes.

Why?

Because they refused to honor God for generations. They mocked his prophets. They indulged in sin for years.

But God is not mocked. What a nation sows, it will also reap.

The exilic books are a record of what life under judgment looks like for the people of a fallen nation, a people without a homeland.

The Babylonians deported a significant number of the Israelites, including the ruling elite, skilled artisans, and influential individuals. They were exiled to Babylon and barred from their own country.

God made it clear through the prophet Jeremiah that this was going to be the way for 70 years.

But in Jeremiah 28, we read about the false prophet Hananiah. Claiming to speak for God, he told the people what they wanted to hear:

Thus says Yahweh of hosts, the God of Israel: I have broken the yoke of the king of Babylon. Within two years I will bring back to this place all the vessels of Yahweh’s house, which Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon took away from this place and carried to Babylon. I will also bring back to this place Jeconiah the son of Jehoiakim, king of Judah, and all the exiles from Judah who went to Babylon, declares Yahweh, for I will break the yoke of the king of Babylon.

Then in vv. 15-16 we read this…

And Jeremiah the prophet said to the prophet Hananiah, “Listen, Hananiah, Yahweh has not sent you, and you have made this people trust in a lie. Therefore thus says Yahweh: “Behold, I will remove you from the face of the earth. This year you shall die, because you have uttered rebellion against Yahweh.”

So Hananiah lies. He tells the people that this is going to be a short stay. He tells them that God will give them victory. They will overcome Nebuchadnezzar. And they will be back home before they know it. So don’t get too comfortable.

Hananiah was a prophet of false hope. And in trying times, in times of crisis and upheaval, people are attracted to these messages—even if they go against all rational thoughts.

But what happens when false hope fails you? Usually, you are even more discouraged and disheartened. And this makes you vulnerable for a different type of false prophecies.

False prophecies of “doom and gloom.”

People desire the outside world to agree with their internal emotional state. It confirms that what they feel is right. It’s a way of coping. It’s a way of avoiding difficult realities. It’s a way of justifying giving up.

If it’s all about to end, why do anything?

In this sense, prophets of false hope and prophets of false doom are two sides of the same coin.

They both peddle a message of self-confirmation that encourages inactivity.

One says, “It’s all gonna be all right, no need to do anything. Just sit tight. Trust the plan.”

What is the plan? It’s almost always some vague promise of deliverance through near-supernatural means.

The other says, “It’s all gonna fall apart. There's nothing you can do. You can’t stop their agenda. Run and hide.”

Who are they? Well, them. The vague group of people in a smoke-filled room who have been planning and plotting all this for years.

Obviously, false hope and false doom don’t mean that there’s no such thing as real hope and real doom. We believe in real hope—and we believe that there are real conspiracies of evil. How could a student of history and scripture believe otherwise?

But we live in an age of intense propaganda. The media will tell you what you want to hear if you keep watching and listening. False hope or false doom. If it gets clicks and views, whatever. They don’t care. They just want your attention.

Remember how intense and weird things got after Trump lost the election? We knew sensible people go deep in the QAnon stuff. They were terribly discouraged by the Biden election. All normal people were. But in that discouragement, they were duped by prophets of false hope.

For example, the prophesied event called The Storm.

According to QAnon, “The Storm” was some future moment when Trump, supported by military forces, would expose and bring down a global cabal of powerful elites involved in various evil activities like child trafficking and satanic rituals.

QAnon followers expected this event would lead to a mass awakening and a restoration of power to those loyal to Trump.

But it didn’t happen. Were their aspects of their claim that were true? Sure, some of the stuff about evil elites. But there was no triumph. No restoration of power. The core message was a lie.

Prophecies of false hope.

What about false doom? Back in early 2021, just after it became clear that Trump wasn’t retaking power, the claims of total societal collapse gained a lot of steam.

There was going to be a mass food shortage. There was going to be a fuel shortage. They were going to shut down the internet.

How many of these things came true? Almost none. So why was it in the media? Why did otherwise sane, rational people buy into it and promote it?

First, it gave disheartened conservatives the content they desired. Not in the sense that they wanted society to collapse. But in the sense that it (falsely) confirmed a correspondence between how they felt, and what was happening. It told them their feelings matched reality.

Second, it was a clever demoralization campaign. It prevented useful action, because why bother?

It seems quite clear now that if Western society is collapsing—and it is—it’s not going to look like an apocalyptic movie.

It’s going to be a much slower decline. That’s what really happened in Rome.

Just because you can move fast doesn’t mean you should

In Proverbs 21:5, Solomon warns us:

The plans of the diligent lead surely to advantage, but everyone who is hasty comes surely to poverty.

“The hasty man,” says Charles Bridges, “is driven under a worldly impulse into rash projects.”

Matthew Henry writes that these types of men are “rash and inconsiderate in their affairs, and will not take time to think.”

Like Icarus, they fly too close to the sun of their inability. The heat of reality is sure to bring them crashing down—but not all at once. The wax melts slowly.

From afar, hasty men can seem like quick studies, or even prodigies. But under the rays of the sun, the words of Jeff Shaara prove true: “Quick words [do] not always mean a quick mind.”

Again, Henry explains, “their thoughts and contrivances, by which they hope to raise themselves, will ruin them.”

The hasty man dreams of ascending the mountain peaks, only to tumble down a ravine for lack of preparation.

The diligent man, however, may be slow, but he is steady. Bridges explains, “The patient plodding man of industry perseveres in spite of all difficulties; content to increase his substance by degrees, never relaxing, never yielding, to discouragement.”

He is a man who understands that haste is the enemy of lasting progress and stability.

He is a man who knows most shortcuts are actually detours.

He is a man who isn’t taken in by the grandeur of rash projects.

As Bridges puts it, he knows that “excitement is delusion, and ends in disappointment.”

Thus, the diligent man is deliberate in plans and pace. The Icaruses of the world may impressively outpace him for a season. But this doesn’t concern him, because he knows that God has determined that “the plans of the diligent lead surely to advantage.” So with joy he relentlessly plods towards his goal.

Hastily-built structures seldom last long, and are of little value against a storm.

Hastily-made vows easily end in divorce and heartache.

Hastily-ordained men often shipwreck their faith—and the faith of others.

Hastily-acquired knowledge produces arrogance, which makes a man a fool.

Flee haste. The internet has greatly increased our capacity for it, and so it is a greater danger now than it was in times past. Our ability to run faster than ever through shallower water than ever has prevented many from learning to swim.

New content

Bnonn and Smokey's new podcast is live. If you're interested in re-enchanting the West, check it out. It’s 50% Smokey's historical and cultural knowledge, 50% Bnonn’s hermeneutical and symbolic insights, and 100% re-enchantment juice for Reformed Christians:

What the heck is “true magic,” you may ask? There’s an episode for that too:

Basically, this podcast is about asking: How should we live in light of the fact that the form of everything we do and are means something?

If you enjoy watching deep-dive videos into random interesting topics on YouTube, and/or you enjoy much of the theological content in this newsletter, you will enjoy True Magic. And if you enjoy it, don’t forget to rate it.

If you prefer a podcast app (who doesn’t?) here are some links:

Or, you can just copy the podcast’s RSS URL into your podcast app, to subscribe directly to the feed: https://api.substack.com/feed/podcast/1143240.rss

Bnonn talked about masculinity and the church with Jason Estopinal on the Laymen's Lounge podcast.

Michael talked about being unapologetically manly with James Hall of the Restoring Heroes Project.

Notable

It's Good to Be a Man got mentioned on The Babylon Bee's podcast episode with Senator Hawley:

His understanding of gravitas is nearly identical to what we write in the book:

Gravitas is, essentially, an effect of developing virtue, which finds its source in God, and thus conforms you to his image. This virtue is gained by practicing the duties that God has given you, and these duties are tied up in working toward the mission that He created you for. We will be so bold as to say that an unbeliever can only ever develop gravitas inasmuch as he emulates the kind of virtue that comes from devotion to the mission of God.

Until next time,

Bnonn & Michael