Leadership is the capacity and will to rally men and women to a common purpose, and the character which inspires confidence.

—Lord Montgomery

You can get more out of men by delegating large tasks to them, as opposed to small ones.

Just hand it off, and go on doing your own work.

If a man doesn't do it, or does it poorly, then you know he can't be trusted at that level yet.

But most men will rise to a challenge. When treated with respect, they are likely to do an equal, or even better job, than you would.

They only need the opportunity to shine.

Principles of godly decision-making

Scripture establishes four principles for decision-making in accordance with God’s will.

Obedience: Where God commands, we must obey.

Freedom: Where there is no command, God gives us freedom (and responsibility) to choose.

Wisdom: Where there is no command, God gives us wisdom to discern what is the best choice.

Faith: When we have chosen, we must humbly trust and rely on the sovereign God to work all the details together for good.

A fifth principle is related. It comes alongside the decision, and must inform the decision:

Thanksgiving: When we have a decision to make, we receive it with thanks for the opportunities it brings; and when we have made it, we thank God for the choice we have selected. Thanksgiving is a kind of governing principle, because it can never truly be applied in cases where we have chosen what is wrong. Sin is deceitful, so we can easily combine the principles of freedom and wisdom to rationalize choices that appeal to our flesh, but are ultimately ungodly. Think TGC-style attitudes to Fifty Shades of Grey.

Chew your food, redux: wisdom v. hot-takes

At the risk of being so meta that I disappear into a recursive pocket universe, I think a “culture of hot takes,” like that stirred up on the place of Twits, is antithetical to a culture of true wisdom.

Hot takes are to wisdom as junk food is to dinner. They are not *not* food, and they are more immediately gratifying—but they are too light and basic to provide anything to chew on, or sustain you long-term.

Or, to vary the analogy, since hot takes often contain genuine insights: hot takes are to wisdom as grapes are to wine. There’s nothing wrong with eating or sharing grapes occasionally. But if you eat all your grapes, instead of spending time breaking them down, storing them carefully, and letting them mature, you will never have any wine.

Social media encourages a culture of grapes, or at best grape juice. Most people, most of the time, would serve both themselves and others better if they wrote down their hot-takes in a PKM system instead of in a post (Bnonn uses Obsidian; Michael uses Apple Notes)—and spent time ruminating on the implications, and applications, beyond the immediate flash of the obvious.

Why not both? It’s not impossible. But in our experience, there is something about impulsively sharing fresh, non-matured insights that works against a pattern of life that also produces developed, mature insights. There seems to inevitably be a balance toward one or the other.

Many people are unable to accurately hear what others are actually saying

The problem isn’t that Johnny can’t read. The problem isn’t even that Johnny can’t think. The problem is that Johnny doesn’t know what thinking is; he confuses it with feeling.

—Thomas Sowell

There are people who never said the things you think they said.

There are people who don’t hold the positions you think they hold.

Sometimes this is due to their lack of clarity.

But often it is because of your lack of clear thinking and reasoning.

We have noticed a frequent inability of readers (or listeners) to comprehend what is actually being said—not because the statements are unclear, but because the reader’s own mind is unable to disentangle his own subjective impressions from the objective words being used.

This is usually due to a combination of associative thinking and emotional reasoning.

1. Associative thinking

This occurs when you make immediate connections between something said, and something else (not said), and fail to notice that the connection exists not in the text but in your mind. You allow yourself to play a game of “free association,” automatically linking up ideas, thoughts, observations, sensory input, memories, existing knowledge, and whatever is churning in your subconscious.

Now, we are not against free association. Bnonn teaches a copywriting course (relaunching soon if you’re interested) in which he argues that “creativity” is actually just the ability to make connections that other people haven’t made. Similarly, what we have said in the past about wisdom being pattern recognition relies on the ability to make intuitive, analogical connections—and scripture itself models this for us in how it is written (e.g., what is the connection between physical light in Genesis 1 and spiritual light in John 1?); and how it interprets itself (e.g., Hagar and Sarah are two mountains, two covenants in Galatians 4:21ff). So connective thinking plays an important role in creativity, and even in reading comprehension, when you know what the author (e.g., God) intended for connections to be made that are not explicitly stated.

But it can be a massive impediment to comprehension in the exchange of ideas, if those connections aren’t intended. And in most writing (or speaking) in Western society, the intended connections are always stated explicitly unless subtle humor or irony is involved.

Take the word “dominion,” for example. Many people associate it with “domination”—and some even associate that word with the practice of BDSM. But dominion and domination are two different things, and have two different meanings. And even those two meanings would need to be read in context to determine their particular usage.

This requires a disciplined mind: a mind that doesn’t wander and freely associate. Unfortunately, such minds are rare in a hyper-referential age. Thus, you can use the word “dominion” in a well-crafted sentence or paragraph, and the reader is now thinking about leather and whips.

Or, the other day Michael mentioned that theonomy played no role in his leaving the PCA and joining the CREC. He also said he didn’t like Rushdoony that much. The immediate assumption was that he therefore wasn’t a theonomist.

Why? Because of associative thinking. Theonomy is linked with the CREC and Rushdoony in many people’s minds. Yes, there is an association—but so what? Nothing in his two statements necessitates the conclusion that people drew.

This is similar to the Newman Effect, named after Cathy Newman’s infamous interview with Jordan Peterson:

“It’s good to be a man.”

“So you’re saying it’s bad to be a woman.”

“We should endure suffering like Christ did.”

“So you think it’s Christ-like to make people suffer.”

Etc. We have the same problem with the word patriarchy. Even if we explicitly say there is good patriarchy and bad patriarchy, this distinction just gets silently dropped on the way into some people’s brains. For them, there is only bad patriarchy. Or, sometimes, only good patriarchy.

But the problem is more widespread than mere “trigger” words. Trigger words exacerbate the effect, but the cause is the undisciplined, unnoticed free association and conflation between what is said, and what is already in the reader’s mind.

2. Emotional reasoning

This is where you are so strongly influenced by your emotions that you assume they indicate objective truth. A classic example is when you assume that, because what you heard made you angry, the speaker was intending to stir up trouble.

Or, perhaps worse, because a statement makes you feel good, therefore it must be true.

Your feelings serve as the interpretive grid for determining the meaning of statements.

Think how disastrous this can be when paired with associative thinking. If a sentence has a word in it which provokes a negative association, you’ll be driven to assume the speaker intended that negative conclusion, regardless of his intent, and even though it really has nothing to do with what he is saying. The word makes you think or feel something, and that comes to dominate your interpretation.

For today’s readers, too often subjects, verbs, and objects matter very little. Indefinite and definite articles become mentally interchangeable. The context isn’t the grammar or syntax of the sentence or paragraph—it’s the entire experience of the reader himself. His individual associations and emotions become the arbitrator of meaning.

We see this in liberals and in conservatives.

We see it in broadly evangelical believers and in strongly reformed believers.

We see it in men and in women.

This is our age.

Communicators must keep this in mind. But readers and listeners must grow in their listening and reading comprehension, or they will forever be trapped in a personalized echo-chamber.

How scripture models public conflict

John Stott's comments on Galatians 2:11-21 are a stiff rebuke to the modus operandi of modern ministries:

Paul did not hesitate out of deference for who Peter was. He recognized Peter as an apostle of Jesus Christ, who had indeed been appointed as an apostle before him (1:17). He knew that Peter was one of the “pillars” of the church (verse 9), to whom God had entrusted the gospel to the circumcised (verse 7). Paul neither denied nor forgot these things.

Nevertheless, this did not stop him from contradicting and opposing Peter. Nor did he shrink from doing it publicly. He did not listen to those who may well have counseled him to be cautious and to avoid washing dirty theological linen in public. He made no attempt to hush the dispute up or arrange (as we might) for a private discussion from which the public or the press were excluded. The consultation in Jerusalem had been private (verse 2), but the showdown in Antioch must be public. Peter's withdrawal from the Gentile believers had caused a public scandal; he had to be opposed in public too.

Paul's opposition to Peter was both “to his face” (verse 11) and “before them all” (verse 14). It was just the kind of open head-on collision which the church would seek at any price to avoid today.

Two takeaways:

We should be willing to give public rebukes for public sin. This is hard for many men; perhaps too easy for a few.

We should be willing to receive public rebukes for even potential public sin. This is hard for everyone.

Reformed culture is a percentage of a percentage of a percentage of what most people think is normal

It seems that most American Reformed Christians have no sense at all of how small the American reformed church is, compared to both other denominations, and the general population.

The Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) is the largest explicitly reformed conservative denomination. Its total membership is approximately 350,000.

That’s big in comparison to the OPC (≈ 33,000).

It’s even bigger in comparison to the CREC (≈ 13,000).

So Michael’s denomination, the CREC, is just under 4% the size of the PCA.

But the liberal PCUSA’s total membership is ≈1.1 million.

So the PCA is only a third the size of the PCUSA.

The SBC has around 13.5 million in membership.

So the PCA is about only 3% the size of the SBC.

And, of course, the total population of the States is around 332 million.

So even the SBC, which has a very difficult general culture to “Reformed America,” only represents about 4% of the total population of the country.

All this to say:

Most reformed denominations represent a percentage of percentage of a percentage of percentage of the national—and therefore “normal”—population.

A week or two ago, Michael mentioned that he knew of a pastor who ripped off Tim Keller’s sermons. Lots of comments were like, “Why Keller? How about a non-woke person to copy.” But it’s simple: outside of a small subsection of a tiny fraction of American Christianity, Keller is still highly respected.

Most reformed folks don’t realize how strange and foreign their terminology, positions, and culture are to most everyone outside their tiny, tiny pond. Michael used to sell mobile phones. He consistently outsold a lot of his co-workers, not because of better product knowledge, but because he spoke the customer’s language. His colleagues loved to use all the technical terminology when describing what various phones could do. “This phone has a 1.3 GHz dual core 32-bit CPU,” or, “The new camera has an 8 megapixel iSight back-side illuminated sensor and sports 1080p HD video at 30 frames per second." This sort of language appeals to phone geeks, but intimidates normal folks. They would think, “I probably should do more research before making a decision,” and leave the store—then end up buying somewhere else the next day. Michael would just say things like, “It’s twice as fast than the last model,” or, “The camera is 30% better than what you’ve got now.” It was accessible language that captured the main idea. It made the decision-making process easier.

With this in mind, it’s important to understand that many Reformed churches and denominations stay small, not because they are super hardcore, but because they struggle to be relatable to, and understood by, the people outside their niche of niche subculture. They are unwilling to place themselves into the experience of those outside their immediate subculture, and meet them where they’re at. But think about how Jesus spoke to the crowds of peasants who came to him. He used simple words, short statements, relatable analogies, and concrete stories. He avoided a lot of jargon, technical terms, and complex statements. It obviously wasn’t because he couldn’t hold his own as a theologian. He is omniscient. His Spirit inspired Romans and Hebrews.

Notable:

NEUROSCIENTIST: "Disturbing Truth About Porn & Masturbation" | Andrew Huberman | Jordan Peterson:

At the end of this video, Huberman offers the following as a highly functional schedule:

Sunlight & movement

Task completion

Thoughtful, reflective

Repeat 1-3

Sleep

He also talks about the importance of relating.

We would expand this a little based on a liturgical pattern modeled in scripture, which starts in the creation but culminates especially in the Lord’s Supper. This is a fractal pattern that repeats at every level of the day:

Grasp: “Jesus took bread…” Take hold of what you are doing, whether in your mind, or in the world (planning stage v. executing stage).

Bless: “…and when he had given thanks…” Receive with thanksgiving what God has given you to do. Note that the inclusion of this step correlates with principle 5 at the beginning of this newsletter. This is the step which is always omitted when work is not oriented in service to God. Adam did not give thanks when he took and ate the forbidden fruit—how could he?

Restructure: “…he broke it…” This is the actual work, again, whether in planning or doing. You break down the task and decide what must be done; then you do the task, which involves breaking apart, using up, tearing down, recombining, etc.

Share: “…and gave it to his disciples, saying, Take, Eat…” At the planning stage, this might involve allocating the tasks you have broken down. After execution, it might involve inviting others to participate in your finished work.

Appraise: “This is my body, which is given for you.” At the planning stage, this might involve prioritizing tasks; after execution, it might involve you and/or others assessing or judging to see whether it is good. Essentially you are judging what the thing now means.

Consume: When the disciples receive the bread, they eat it. This step might mark the transition between planning and execution (remember, the pattern repeats), or it might mark the transition between assessing the finished work and enjoying it. Essentially, you are integrating the work with the rest of your life, which can take many forms.

Sunlight and movement is not on our list, because that would be a category error. That’s a “how” question, not a “what” question. It can and should be included at any point that makes sense.

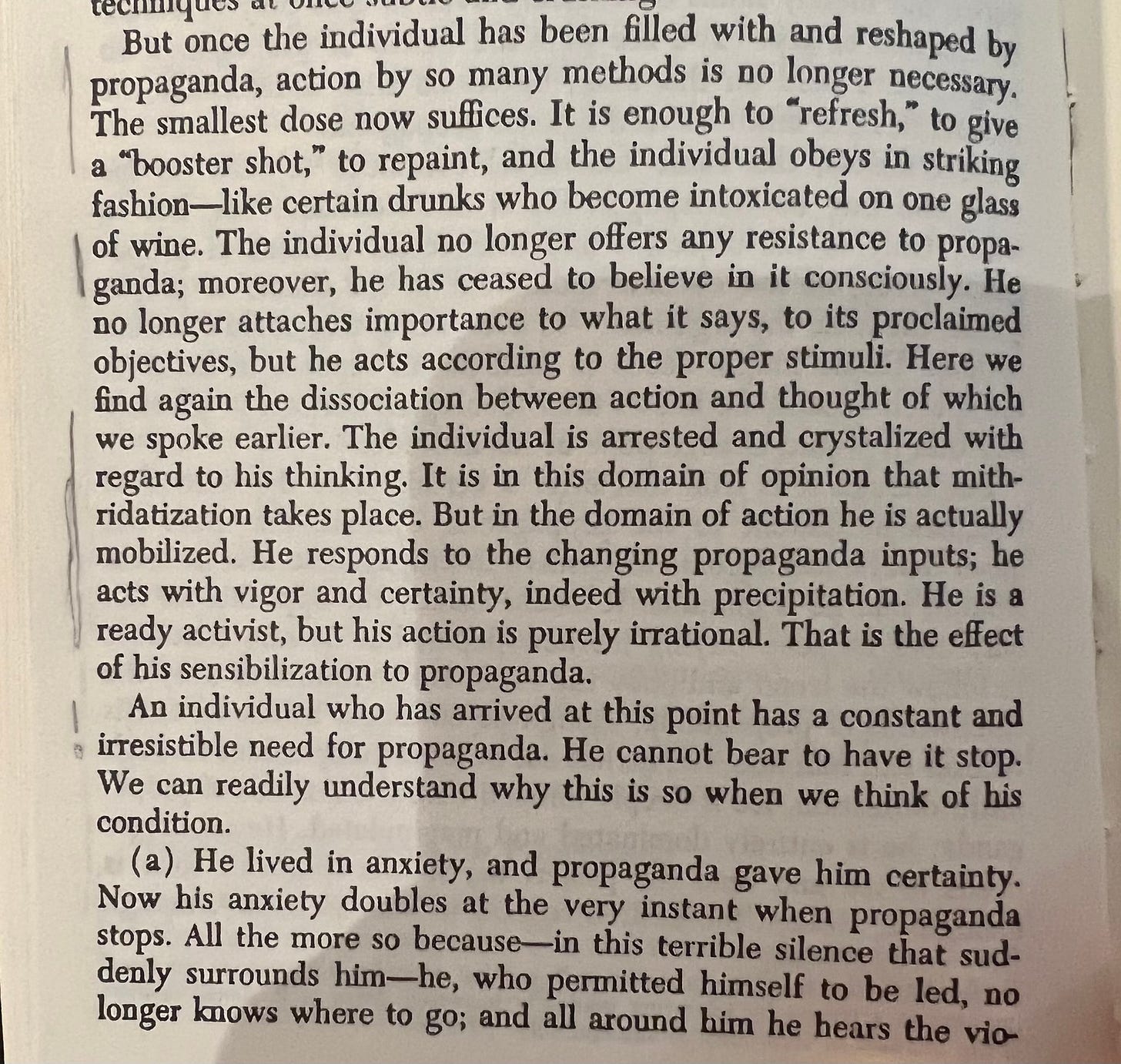

Dr. J. Woods shared this prescient section from Ellul's Propaganda (1973):

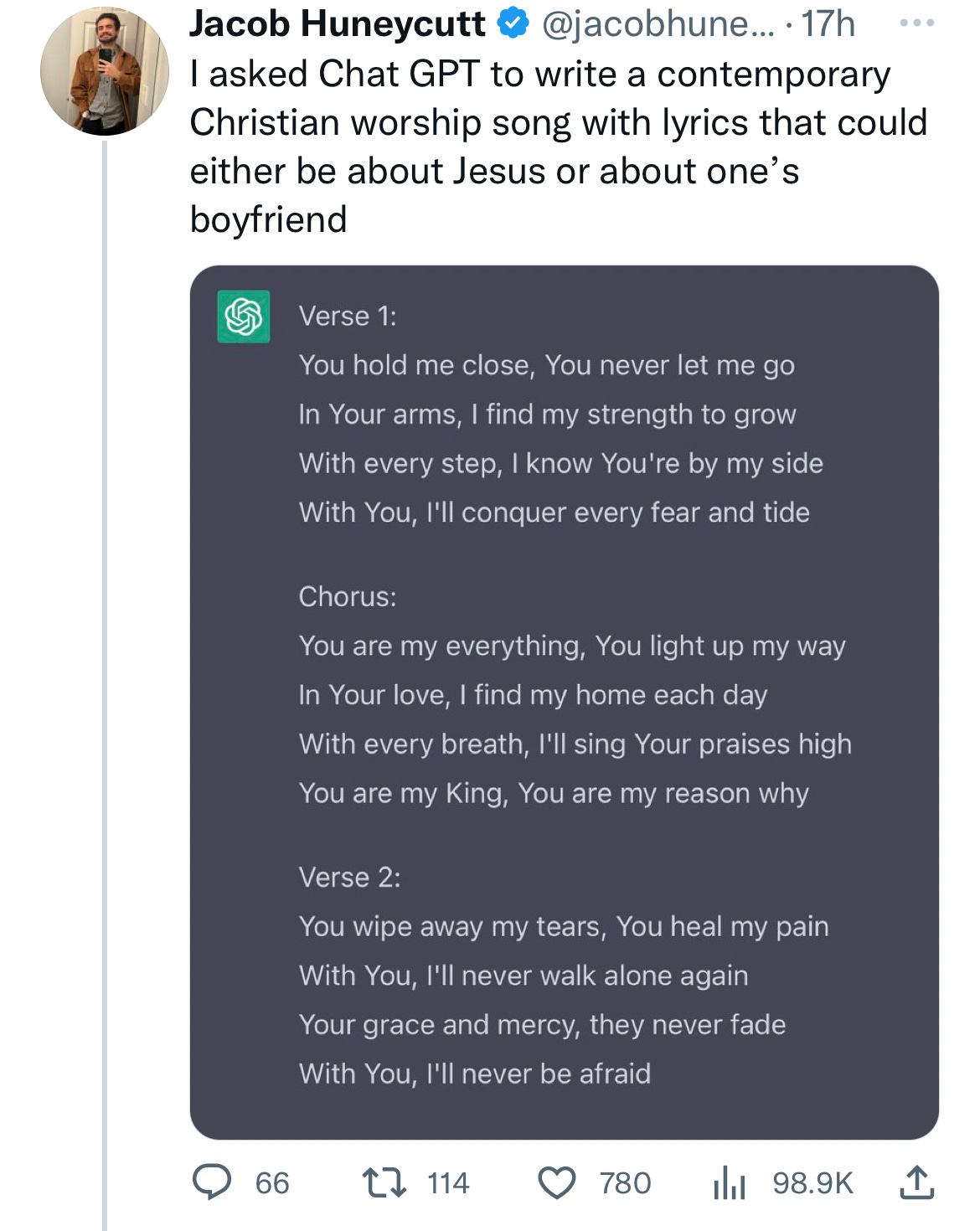

Better than 90% of CCM:

Stay for the mug at the end:

Talk again next week,

Bnonn & Michael