Martin Luther famously nailed 95 theses to the church door in Wittenberg.

Less famously, but very importantly, his first thesis was:

Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, in saying, “Repent ye, etc.,” intended that the whole life of his believers on earth should be a constant repentance.

Our newsletter is called Discipleship and Dominion after a very similar conviction: that the Christian life is fundamentally about being conformed to the image of Christ (discipleship), so that we may rule with him (dominion). “If we do endure together—we shall also reign together” (2 Ti 2:12).

Today we want to talk about the former part of this, expanding on Luther’s thesis.

In Acts 2, having heard the gospel from Peter, the Jews were pierced to the heart and said, “What shall we do, men, brothers?”

And Peter said unto them, “Repent, and be baptized.”

You might think that being pricked to the heart showed that they had repented. But if that were the case, Peter would not need to tell them to repent. So repentance is not mere sorrow over sin. Sorrow is necessary for repentance, but it is not repentance. And not just sorrow is needed, but Godly sorrow. Have we not all felt sorrow and shame and even terror over some sin—but all that regret is really just because of its consequences? We think, “I wish I had never done that”—yet we do not mean, “I wish I had never sinned,” but rather, “I wish my sin had never affected me thus.” We would do the sin again, eagerly, if we knew it would not affect us.

This is not a sorrow that produces repentance, but a sorrow that produces death. Paul describes the clear difference in 2 Corinthians 7, as he tells the Corinthians that not only does he not regret hurting them with his rebukes, but that he rejoices that he hurt them:

I now do rejoice, not that ye were made sorry, but that ye were made sorry unto repentance, for ye were made sorry toward God, that in nothing ye might suffer loss by us; for the sorrow toward God worketh repentance unto salvation, unregretted, but the sorrow of the world worketh death, for, look, this same thing—to have been made sorry toward God—how much diligence it hath worked in you! what desire to clear yourselves, what agitation, what fear, what longing, what zeal, what avenging; in every thing ye did set forth yourselves to be pure in the matter. (2 Co 7:9–11)

In other words, Paul says, rather than just being sorry at being caught, rather than being ashamed of being reprimanded, the Corinthians, who were true Christians despite their many failings, were made sorry toward God. They were cut to the heart that they had offended the Lord, and out of their love for him, they were diligent to repent. Their sorrow toward God worked changes in them. “In every thing ye did set forth yourselves to be pure in the matter.”

This is the work of repentance: seeking after purity from the sin committed. But how do we go about this work of repentance, of making ourselves pure before a holy God? What can we possibly do?

The beginning of repentance

David instructs us that we begin with a plea:

Be gracious to me, O God, according to thy covenant-love,

According to the abundance of thy mercies blot out my transgressions.

Thoroughly wash me from mine iniquity,

And from my sin cleanse me (Ps 51:1–2)

Repentance begins by falling on the mercies of God. It does not end there, but it begins by appealing to God’s covenant-love—his lovingkindness, his steadfast-love, his chesed; a word for which there is no good English translation, but parts of it are all captured by these English phrases. It is because of God’s goodness, God’s love, God’s covenant promises, God’s unfailing faithfulness, God’s overflowing mercy, that David can come before him, seeking the undeserved help that he needs. It is God who must wash him, God who must cleanse him, God alone who can pardon him, because ultimately as David goes on to confess in verse 4, it is God only against whom he has sinned.

He does not mean, of course, that he did not sin against Uriah and Bath-Sheba, and indeed all the palace servants that were implicated in his plot, and in fact against the whole of Israel over whom he was head, and whom he had failed as king in God’s stead. But he means that God is the one whose law he has broken, and by sinning against the image of God, he has sinned against God himself. Our sins against other men are simply means by which we sin against God—the rights they have which we violate are rights granted by God, and so every sin against them is really a sin against him.

But falling on the mercies of God also entails something else, taken for granted in the psalm but often spelled out in scripture as essential to repentance: a turning toward God.

And also now—a declaration of Yahweh—Turn ye back unto Me with all your heart, and with fasting, and with weeping, and with lamentation. And rend your heart, and not your garments, and turn back unto Yahweh your God, for gracious and merciful is He, slow to anger, and abundant in covenant-love (Joel 2:12)

To repent is to turn back to God from your sin. It is not only this, as we shall see, but this is a critical part of it. One must actually come to God as David does at the beginning of the psalm. “Draw near to God, and he will draw near to you,” James tells us. And we draw near to him out of the sorrow we have toward him, rending our hearts, tearing at the sin within us, appalled at it as with a tumor bursting from our skin, wanting to rip it out for the sake of being pure.

But there is more going on. Repentance is not just an event in response to the event of sin. It is a transformation in response to a sin nature. David in Psalm 51 confesses that his sin was not some freak occurrence, but the natural issue of a corrupted heart. “Look, in iniquity I have been brought forth, and in sin doth my mother conceive me.” As Calvin so rightly says,

Filled with shame for a recent crime he examines himself, going back to the womb, and acknowledging that even then he was corrupted and defiled. This he does not to extenuate his fault […he] makes it an aggravation of his sin, that being corrupted from his earliest infancy he ceased not to add iniquity to iniquity. In another passage, also, he takes a survey of his past life, and implores God to pardon the errors of his youth (Ps. 25:7).

And again, Calvin says,

For the flesh must not be thought to be destroyed unless every thing that we have of our own is abolished. But seeing that all the desires of the flesh are enmity against God (Rom. 8:7), the first step to the obedience of his law is the renouncement of our own nature. (Calvin, Institutes)

In other words, David is not using, “I was born this way,” as an excuse for his sin, but rather as a vindication of God’s judgment. He says, in effect, “Not only have I committed this heinous deed, murdering my friend to cover my adultery with his wife, but in fact this was natural to me, this flowed out of a nature which from birth has been wicked, and has craved such wicked things—and would do far more and far worse again at every opportunity, if not for the grace of God restraining it and protecting me from these evil and corrupt desires.” David knows that every working of the thoughts of man’s heart is only evil all the day (Ge 6:5).

He therefore comes before the Lord, seeking his help, being utterly helpless not only to save himself from the judgment due his sin, but to save himself from the very nature that would continue to commit such sin if it had its way. He turns not just from his sin to God, but from his sin nature to God.

But falling on the mercy of God, confessing our depravity and seeking his pardon, is not the extent of repentance. It is only the beginning, the entrance to repentance. The fullness and center of repentance is found in center of Psalm 51. David works in toward this center—see how he describes this inmost, fundamental aspect of repentance:

The heart of repentance

Look, truth thou hast desired in the inward parts,

And in the hidden part wisdom thou causest me to know.

Thou cleansest me with hyssop and I am clean,

Washest me, and than snow I am whiter.

Thou causest me to hear joy and gladness,

Thou makest joyful the bones thou hast bruised.

Hide thy face from my sin,

And all mine iniquities blot out.

A clean heart prepare for me, O God,

And a right spirit renew within me.

Cast me not forth from thy face,

And thy Holy Spirit take not from me. (Ps 51:6–11)

On the face of it, these seem like oddly haphazard and unrelated things. In verse 6, God desires truth in the inward parts, the heart—and so he causes David to know wisdom. In other words, he puts the truth there that he desires. It is not David who causes himself to know truth and wisdom, but God. But then verse 7 seems to change topic. It speaks of being washed, being cleaned, being made whiter than snow. Then verse 8 seems to change topic again. God causes David to know joy. Then verse 9 seems to change topic again, asking God to hide his sin and blot it out, or wipe it away. Then he changes topic again. Verse 10: “a clean heart prepare for me, and a right spirit renew within me.” And then verse 11 seems different again, about God not casting him away.

But if you pay careful attention, David is actually describing one and the same thing from several angles. He is describing what God has done, and is asking God to continue to do it; and it is something that involves becoming truthful, or even becoming true; becoming clean; becoming joyful; having his sin wiped out; having a clean heart; having a right spirit; remaining in God’s presence; and continuing to have his Holy Spirit.

In other words, while you probably identified quite easily that verse 10 is about regeneration in some sense—the new birth—in fact all of these verses are about that. It is regeneration that gives us truth and wisdom in our inward parts for, “we have the mind of Christ” (1 Co 2:16). It is regeneration that washes us and makes us clean and wipes out our sin and gives us the Holy Spirit—“he did save us, through a washing of regeneration, and a renewing of the Holy Spirit, which he poured upon us richly, through Jesus Christ our Saviour, that having been declared righteous by his grace, heirs we may become according to the hope of life eternal” (Tit 3:5). It is regeneration that gives us joy. “And the fruit of the Spirit is: Love, joy, peace…” (Ga 5:22). And it is regeneration by which we are not cast from before Christ’s face, but instead can see his kingdom—“all that the Father doth give to me will come unto me; and him who is coming unto me, I may in no wise cast out…no one is able to come unto me, if the Father who sent me doth not draw him, and I will raise him up in the last day” (Jn 6:37, 44).

In other words, repentance is not just about turning away from our sinful nature in sorrow, not just about turning toward God for help—it is about the complete transformation of our nature that takes place through that help. This is greatly obscured by the insistence of modern Bibles of translating the Greek word, which is metanoia, as repentance, rather than as what it actually means: mind-change. To repent is change mind. Not to “change your mind,” as a mere altering of opinion or correcting of a belief. To change mind is not to change a tiny piece of your mind; some concept or idea contained within your mind. Rather, it means to change your entire inner being. It is referring to a transformation of the heart.

This is why scripture often speaks of repentance as something that must be given by God. For instance, in Acts 11:18, the people glorify God saying, “Then, indeed, also to the nations hath God given the repentance [mind-change] unto life.” In the same way, 2 Timothy 2:24–26 gives God all the credit for repentance, telling us that

it is necessary that the Lord’s slave must not fight, but be gentle unto all, apt to teach, patient under evil, 25 in meekness instructing those opposing—if perhaps God may give to them repentance [mind-change] unto an acknowledging of the truth, 26 and they may awake out of the devil’s snare, having been caught by him unto his will. (2 Ti 2:24–26)

A complete alteration of the inner man is impossible for us, for the inner man hates God and wants nothing to do with him, and doesn’t want to change. Only God can give us a new heart:

And I have given to them one heart, And a new spirit I do give in your midst, And I have turned the heart of stone out of their flesh, And I have given to them a heart of flesh. 20 So that in My statutes they walk, And My judgments they keep, and have done them, And they have been to me for a people, And I am to them for God. (Ezek 11:19–20)

We must not confuse repentance and regeneration. We are only regenerated once. But David says, “a clean spirit prepare for me, O God, and a right spirit renew within me.” Certainly he was regenerate when he wrote this. So certainly, while regeneration is indeed a one-time event that definitively changes our nature, it is not a complete event; it does not perfect our nature; it does not leave nothing more for us to do. It is the beginning of our sanctification, not the end of it. Calvin calls regeneration initial sanctification; the punctiliar act by which we become completely different creatures, holy creatures. But after that point, as completely and holy different creatures, we must grow and mature in that new holy nature we have received. We must, indeed, continue to receive it. We must be transformed by the renewing of our minds, and this is something that happens over time, by study of God’s word, and practice in it.

Practicing repentance

The gnostic tendency of our day is to reduce this mind-change to intellectual study. But even the mind of the flesh can intellectually study and comprehend God’s law. The demons believe, though they shudder—and to believe they must understand. Repentance, however, involves the will and the affections; not merely the mental machinery that analyzes and remembers data. It involves our moral faculties, not just our intellectual ones. It is true that our whole mind is corrupted by sin, so even our intellectual faculties do not work as they ought…yet James tells us that the demons nonetheless have minds functional enough to read God’s law and memorize it and repeat it back to you and explain what it means and why it terrifies them. Satan can probably deliver a better lecture on any part of scripture than the best theologian who has ever lived—because he is very smart, and very experienced, and has had thousands of years to memorize and analyze the scriptures.

But what he will never be able to do is grasp them in a moral sense. He cannot receive them in even the most childlike, rudimentary way. He cannot appreciate them as even a day-old convert does. Even a regenerate baby, who cannot intellectually grasp God’s law at all, knows that law better than Satan, because his tiny, barely-formed mind is fitted to receive that law rather than reject it.

To put it in very simple English terms, Satan might believe that God’s law is true—but he does not believe in God’s law as truth. He does not give himself to it as something good and beautiful—he only observes it from afar, as propositions, as facts, as premises, as statements. He knows that these premises and propositions are true, in the sense that they correspond to reality. But he does not appreciate them as truth, as something desirable, or lovely, or sweet, or precious. He will not, and cannot, conform himself to their shape.

Of course, it is easy to shake our heads and purse our lips about Satan. Oh, very bad, very bad, how he hates God and his law and everything good. Such a bad guy. So evil.

It is even easy, especially for those of us with some miles under our belts, to do the same thing with ourselves before we were converted. What rotten people we were. How we loved what is vile and false, and how we flinched and recoiled from God. How we eagerly chased after the cravings of our flesh, running with endurance the path down to the pit—and how we rushed not just toward sin, but away from the God behind us, always fleeing his judgment. How we coveted and longed for the things that would bring us temporary pleasure, how we loved the ease of sin—and how we hated the discipline, the hard work required to be good.

Thank God, who put his Spirit within us, and rescued us from the path of destruction, and turned us around, and made us to love good and hate evil, and empowered us to walk in his ways and run the race with endurance. “Our old man was crucified with him, that the body of sin might be done away, so we would no longer be in bondage to sin” (Ro 6:6). “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Ga 2:20). Praise God, we have put on Christ!

But…why then does Paul tell us to keep putting him on? “Put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh, to fulfill the lusts thereof” (Ro 13:14). Or, “put off, as concerning your former behavior, the old man, that is corrupt after the desires of deceit; and be renewed in the spirit of your mind, and put on the new man, that after God has been created in righteousness and holiness of truth” (Eph 4:22–24). Or again, in Colossians, with much force he urges us:

If then ye were raised together with Christ, seek the things that are above, where Christ is, seated on the right hand of God. Set your mind on the things that are above, not on the things that are upon the earth. For ye died, and your life is hid with Christ in God. When Christ, who is our life, shall be shown-forth, then shall ye also with him be shown-forth in glory. Put to death therefore your members which are upon the earth: fornication, uncleanness, passion, evil desire, and covetousness, which is idolatry; for which things’ sake cometh the wrath of God upon the sons of disobedience: wherein ye also once walked, when ye lived in these things; but now do ye also put them all away: anger, wrath, malice, slander, shameful speaking out of your mouth: lie not one to another; seeing that ye have put off the old man with his doings, and have put on the new man, that is being renewed unto knowledge after the image of him that created him: where there is not Greek and Jew, circumcision and uncircumcision, barbarian, Scythian, slave, free; but Christ is all, and in all. Put on therefore, as God’s elect, holy and beloved, a heart of compassion, kindness, lowliness, meekness, longsuffering. (Co 3:1–12)

If God has regenerated us, and united us to Christ, and filled us with his Spirit, and given us his mind; if God has put away the old man of flesh in us, and raised us into the heavenly places to live by the Spirit as new creations…why does he repeatedly, insistently, earnestly, vigorously call us to put off the old man and put on the new?

Why, after he has been given a clean heart and a renewed spirit through the washing of regeneration, does David say, “a clean spirit prepare for me, O God, and a right spirit renew within me”?

It is because we are still living in bodies of death, even though we are alive in the Spirit—and so there is a sense in which we only understand God’s ways as Satan understands them: intellectually. He hates them, he maintains his distance, he will not conform himself to them, he cannot appreciate them. And we are in the strange situation of having one half of us, the natural half of us, the part that was conceived in sin and brought forth in iniquity, having the same feelings. Our flesh loves death, it hates life, and it strains every moment against the Spirit of God within us.

for the flesh desireth contrary to the Spirit, and the Spirit contrary to the flesh, and these are opposed one to another (Ga 5:17)

And what is the result of this? Paul warns us, continuing: “that ye may not do the things that ye want.” In other words, as he puts it in Romans 7,

that which I do, I understand not; for not what I want do I practise, but what I hate, this I do (Ro 7:15)

And again:

for the good that I want, I do not; but the evil that I do not want, this I practise. And if what I do not want, this I do, it is no longer I that work it, but the sin that is dwelling in me. (Ro 7:19–20)

And so he says,

I behold another law in my members, warring against the law of my mind, and bringing me into captivity to the law of the sin that is in my members. A wretched man I am! who shall deliver me out of the body of this death? (Ro 7:23–24)

Of course, his answer is the Lord Jesus—but the method is to put off the old man of death, and put on the new man that is being renewed in mind. It is to war against the flesh that wars against us. It is to know that in our flesh, our hearts are deceitful and incurably crooked above all things, and that we cannot fathom the depths of this corruption (Je 17:9). Therefore, it is impossible to easily put off the old man and our former behavior, which is corrupt after these desires of deceit, and to be renewed in the spirit of our minds. It is a continual work to put on the new man, which after God has been created in righteousness and holiness of truth.

He who is thinking to stand—let him watch out, lest he fall (1 Co 10:12). Sanctification is not an easy process. When God regenerates us, he does not plop us into a nice canoe, and push us off down a gentle creek—and we just occasionally dip the paddle in to stay on course; to steer clear of the occasional rocks; maybe pick up a bit of speed. It is quite the opposite. If this is the analogy to use, then God finds our lifeless corpses being carried down a rushing river, full of rocks and rapids, and he drags us out and breathes life into our dead bodies, and turns us around, and tells us to start swimming back upstream—where we are continually in danger of being sucked back down, where we are continually dashed against rocks, where we are continually discovering new, invisible dangers beneath the surface, where we are continually drowning and needing him to rescue us. There is never any doubt that he will rescue us when we cry for him—but there is also never any doubt that we will have to cry for him over and over and over again, and that every time we think we are in a calm spot, every time we are confident that we’ve got the hang of swimming now, every time we think we are in the clear, we are, in fact, in even more danger than before when the hazards were visible. The Christian who thinks that the river is basically calm, basically clear, the Christian who thinks he knows where the rocks are and how to avoid them, is the Christian who has entirely lost his bearings.

In the same way, the Christian who spies a tranquil cove and swims into it and starts to enjoy it, is a Christian who has lost his way. He is no longer swimming upstream. He is no longer moving toward his goal.

But isn’t that cove so inviting? Doesn’t our flesh long to rest there? Why must we always be swimming, after all? Isn’t it enough that we have been saved, that we are alive? It would be so much easier to float about in that cove, to relax where the water is calm. In fact, hey, there are a bunch of people in there already, calling us over, saying come on in, the water is great! They’re having a good time, they’ve found a protected area where there’s no constant fighting against the current, it looks really comfortable. What could be so wrong with it? They’re not going downstream after all. They’re not going with the flow. They’re just not treating this like some kind of extreme sport, like some kind of race they have to win to attain a prize. It’s not like there’s a finish line. The river goes on up forever. Why should we have to buffet our bodies, striving and slaving away all the time?

But the longer they mill about in that calm water…the longer they float aimlessly…the more like dead bodies they begin to look again.

Truly, our flesh wants to kill us, and it is deceptive—so its most effective weapon is not the great temptations, the desires we feel for obviously sinful things. We see those rocks. It is the weeds under the water that are the greater danger. The most effective temptation of our flesh is to tell us that we have done enough. “You’re justified by faith, not by works,” it will tell you. “You don’t commit big sins. Sure, you’re not perfect, but you never will be until glory. So why not take it easy? Jesus has got you. As long as you keep trusting him in your heart, you’re okay, even if you sin in the body. He loves you no matter what. In fact, he wants you to be happy, not to make yourself miserable.”

It is true that he wants us to be happy. But he wants us to be happy in him. He wants us to learn to love everything that is true and good and beautiful, and to hate everything that would drag us down from that. He wants us to find our comfort and our ease in him—not to add him to our fleshly comfort and ease as Lot’s wife tried to do. Yahweh rescued her out of Sodom, but she thought she could have the rescue, and still yearn after the life she had.

But his wife looked back from behind him, and she became a pillar of salt. (Ge 19:26)

What was life like for her in Sodom? Ezekiel tells us:

Behold, this was the iniquity of thy sister Sodom: pride, fullness of bread, and prosperous ease was in her and in her daughters; neither did she strengthen the hand of the poor and needy. (Ezek 16:49)

Prosperous ease is what our flesh craves, and it will whisper every day to us that this is what God wants for us too. It will try to convince you that prosperous ease is sabbath rest, and that you can just slip into it, rather than climbing the mountain of God to attain it. It will slowly, imperceptibly, start to turn your heart to think, “You know, those Christians who are always working at salvation, always taking things so seriously, always fired up about keeping God’s law…they’re running kinda hot. They’re gonna burn out. And look how cold they can be toward other believers who don’t see things their way. Isn’t that a really negative way to live? Maybe it’s not good to run hot and cold like that. Maybe it’s better to chill out a bit, tone things down.”

There were such Christians in the first century, in the church of Laodicea. But here is what Christ had to say to them:

I have known thy works, that neither cold art thou nor hot; I would thou wert cold or hot. So—because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I am about to vomit thee out of my mouth; because thou sayest, I am rich, and have grown rich, and have need of nothing, and hast not known that thou art the wretched, and miserable, and poor, and blind, and naked, I counsel thee to buy from me gold fired by fire, that thou mayest be rich, and white garments that thou mayest be arrayed, and the shame of thy nakedness may not be shown forth, and with eye-salve anoint thine eyes, that thou mayest see. As many as I love, I do convict and discipline; be zealous, then, and repent [change mind] (Re 3:15–19)

The Laodiceans had become tepid—middle-of-the-road…what today would be proudly called by many, “moderate.” They had a church that outwardly had everything; everyone felt good about it—yet inwardly they had nothing, because they had become complacent in their prosperity. They were no longer waging war against their flesh, and so, as John Owen famously put it, they were no longer killing sin—sin was killing them. Their flesh had convinced them they were good, God had blessed them, there was no need for hard work any more. Why be troubled? They were like the man that C.S. Lewis describes in Mere Christianity, where he says:

When a man turns to Christ and seems to be getting on pretty well (in the sense that some of his bad habits are now corrected), he often feels that it would now be natural if things went fairly smoothly. When troubles come along—illnesses, money troubles, new kinds of temptation—he is disappointed. These things, he feels, might have been necessary to rouse him and make him repent in his bad old days; but why now? Because God is forcing him on, or up, to a higher level: putting him into situations where he will have to be very much braver, or more patient, or more loving, than he ever dreamed of being before. It seems to us all unnecessary: but that is because we have not yet had the slightest notion of the tremendous thing He means to make of us…

Hence, Calvin in his Institutes says of the more mature Christian,

he seems to me to have made most progress who has learned to be most dissatisfied with himself. He does not, however, remain in the miry clay without going forward; but rather hastens and sighs after God, that, ingrafted both into the death and the life of Christ, he may constantly meditate on repentance.

This is the total transformation that Christ calls us to. At every stage of that transformation, we have a very poor view of how far we have yet to go. We can only see backwards, and so we only see how far we have come. This is an extremely truncated perspective that is too easy to take as a full view of reality. As we get older, we learn that in fact there is a great deal more corruption left in us than we initially realized. Yet it is impossible for us to fathom how much. We have only a feeble intuition about it based on past experience—because in order to see the depth of that corruption, we would need a much more transformed mind than we currently have.

It is as if God is gradually removing layers and layers of callouses from our hands, and each time we discover that our fingertips are a little more sensitive, a little more able to feel things we never could before. But because every time we are therefore the most sensitive we have ever been, we still have no conception, no way to tell, what it is like to be more sensitive still. We start to learn that we can be more sensitive, but until we actually experience it, we cannot know it. It is the same with the life of repentance. As our minds are transformed, they become continually more sensitive to truth and beauty and goodness—we feel ever more keenly how lovely they are. And, in contrast, we also become continually more sensitive to falsehood and corruption and sin—we feel ever more keenly how vile they are.

But this process is impossible without a deep investment in it. It is impossible as long as we listen to our flesh, which wants us to accept that a surface-level transformation of our beliefs will do; that transformation of the mind is exhausted in intellectual revision, which may of course issue in some changed behavior, in shedding some bad habits—but once the new beliefs are in place, and a new routine of behavior to match them, the job is petty much done.

The job is not pretty much done.

Our will, our affections, our moral instincts, our aesthetic intuitions, our whole being, down to the core—everything we feel, everything we want, everything we love or hate, everything that pleases or displeases us, everything we long for, everything that makes us happy or sad, joyful or fearful, calm or angry—everything, every one of these, is what God wants to transform. Every one of them is corrupt in some way, because we are wholly corrupt.

God intends to wholly redeem and restore us.

Let me break character and court controversy by offering a particularly pertinent example: The music you enjoy is not neutral. If the true and the good are bound up together with the beautiful, and beauty finds its source and ground in God, then some music is objectively ugly, and some is objectively in need of reformation; and some genres and pieces and songs, even some instruments, are objectively better than others. And God wants to transform your aesthetic intuitions, your affections for beauty, so that your musical preferences align with the objectively true and good and beautiful. I don’t mean that when we are glorified, God is going to make all of us prefer exactly the same music in exactly the same way, any more than he is going to make us like Rembrant more than Michelangelo, or da Vinci more than Monet, or mountains more than forests, or deer more than eagles. He is not after uniformity. But he is after unity. You will like Rembrant and Monet and da Vinci and Michelangelo, because they are beautiful; and you will hate much of what passes for art in modern galleries, because they are not. In like manner, you will appreciate Mozart and Prokofiev and Beethoven because they are beautiful; and you will abominate a lot of what is most popular in your iTunes store—and even in modern churches.

I give this example only as a concrete way to understand that what appeals to our flesh, what makes us feel good in the moment, is not necessarily what God loves. Here is perhaps an even more extreme, yet horribly common illustration: think of how many people have affairs because they convince themselves it feels “right.” How can such strong feelings be wrong? It feels true and good and beautiful—so it must be true and good and beautiful. If only our flesh were not wholly corrupt and deceitful, that would be true. If only our minds were wholly transformed into the image of Christ, that would be true. But while we remain in the flesh, it will “misfeel” all the time.

Whoso is trusting in his heart is a fool, and whoso is walking in wisdom is delivered. (Pr 28:26)

But wisdom only comes from God’s word, and can only be discerned with the help of the Spirit. Hence Solomon tells us again:

Trust unto Yahweh with all thy heart, and unto thine own understanding lean not. In all thy ways know thou him, and he doth make straight thy paths. (Pr 3:5–6)

Or, as James would say,

Be doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving yourselves. (Jas 1:22)

There can be no ceasefire in the war we wage with our flesh. The life of repentance is a life of dying daily to self. We are daily to take up our cross. We are daily to present our bodies as sacrifices. We must run the race with endurance—not with occasional sprints.

This is a hard word.

As Chesterton quipped, “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and left untried.” Yet compared to the burden of sin, the crushing weight of it that drags us down to hell, this yoke is easy and the burden light. There is hardship and sorrow in it, yes, but it is the hardship and sorrow that comes with being disciplined as sons. It is not the sorrow that comes from God’s wrath, but rather from his fatherly displeasure with our sinful and corrupt state, which must be corrected. He is our loving Father, who has given us the mind of his Son, so that we should become like his Son. He loves so much that he gave the life of his Son for us—so he certainly loves us too much not to require us to give up our lives in turn. We are either pressing on, or we are falling back. We are either running the race, or we are dead. Discipleship unto dominion.

He who is overcoming, and who is keeping unto the end my works, I will give to him authority over the nations. (Re 2:26)

Upcoming: Guts & Grace conference

Tickets are now available for the new fall conference series that Michael is organizing: Guts and Grace.

Whereas County Before Country had a broad cultural focus, Guts and Grace will specifically focus on the reformation and revitalization of the church in America.

Christianity requires both guts and grace. Shrill controversialists may have guts, but they lack grace. And cultural appeasers may come off as gracious, but they are just gutless. Only with both can you fight the good fight!

This year, speakers will consider various battles from church history, and provide some lessons that we can apply to our day.

Keynote speakers:

Christopher Wiley

Dr. Joseph Pipa

Dr. George Grant

Grant Castleberry

Michael Clary

Dr. Joe Rigney

Michael and his wife will be hosting breakout sessions—one for men and one for women.

The conference will be emceed by Pastor Zach Hill from Silver City Church.

There will also be a singles mixer event, and a pastors’ luncheon.

Notable:

Some good advice transferable to most domains:

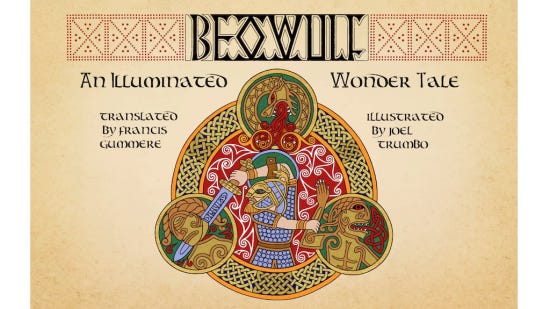

Beowulf: An Illuminated Wonder Tale. An illuminated edition of the Anglo-Saxon epic tale "Beowulf" in Old English and modern English translation.

(Source; HT

)Put these three things together:

This video reveals the anti-repentance mindset within much of the modern church. People writing modern worship music, people considered worship leaders, are routinely asking AI things like, “What does this mean to you,” to make sure their lyrics are getting the right thing across—rather than learning how scripture itself speaks, and conforming their minds, and their audience’s minds, to that. Or, “give me some interesting chord progressions,” instead of thinking through what the sound of a chord progression actually communicates, and what it needs to mean. We have regressed to a childish, simple-minded and industrial approach to art, where objective truth and beauty have been replaced by subjective authenticity and feelings—churning out a product to evoke a certain sensation in the flesh, rather than to transform and renew the mind according to the heavenly pattern. If algorithms can do that more efficiently than an artist, then why not use algorithms?

Truth and goodness and beauty are objective and transcendent, finding their source and ground in God. Worship is supposed to be a participation in that reality. But how—when the expression of our worship, the “glorified speech” that should raise us up to heaven, is not even just carnal, but an algorithmic aggregation of carnality?

The purpose of a system is what it does. —Blake Blount

Talk again soon,

Bnonn