But who does the dishes?

Satisfaction and contentment with the labor of the house is impossible without first recovering God’s design for the house.

This question weighs heavy on the hearts of evangelical pastors and their female congregants—it comes up with surprising frequency in sermon illustrations, marital counseling, and even when we request questions for our Q&A episodes.

“Who should do the dishes?”

Our first thought was, “Really? Who cares?”

But on further reflection, it all started to make sense.

The question of who does the dishes is apparently a source of intense marital contention in many households. Back in 2019, Caroline Kitchner opined in The Atlantic that Doing the Dishes is the Worst. “This is now an empirically proven fact,” she wrote. “Dishwashing causes more relationship distress than any other household task.” She went on to prove her claim:

A report from the Council of Contemporary Families (CCF), a nonprofit that studies family dynamics, suggests that the answer to that question can have a significant impact on the health and longevity of a relationship. The study examined a variety of different household tasks—including shopping, laundry, and housecleaning, and found that, for women in heterosexual relationships, it’s more important to share the responsibility of doing the dishes than any other chore.

Note that dishwashing is the most important chore to share for women in heterosexual relationships. Not men—women. We’ll come back to that. Needless to say, this issue is coming up in many marriages, so it makes sense that guys are asking us the question.

It also makes sense that we’ve noticed many pastors repeatedly calling husbands to help with the housework. We don’t mean exhorting them to mow the lawn, fix a leaky faucet, or take out the trash. What really stands out is the consistent call for men to chip in with the traditionally feminine housework—especially doing the dishes.

So it seems that men are asking us who should do the dishes because (1) their wives care deeply about the issue, and (2) pastors are advocating for their wives’ position.

But why is this an issue? It seems so random. Why do women and pastors care so much about who does the dishes specifically?

As usual, we don’t think it’s ultimately about the physical chore itself. It is about the symbolic meaning of dishwashing, and the changing nature of the household. The physical is merely imaging the spiritual.

The symbolic meaning of dishes

In Dishes: A Preamble to Women’s Work, Elaine Bernstein Partnow, the editor of feminist.com, explains:

Some men do the dishes some of the time. A few men do the dishes all of the time. Most men never do the dishes… Symbolically, the message is very clear. Men, like women, make a mess—but the mess is left for women to clean up.

Partnow is right that doing the dishes is symbolic. But she hasn’t quite understood the fullness of what they represent.

In the mind of the modern woman, they represent the drudgery of the household.

This comes across loud and clear in Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. She writes:

As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘Is this all?’

…And finally there is the problem that has no name, a vague undefined wish for “something more” than washing dishes, ironing, punishing and praising the children.

It seems, however, that Friedan didn’t know as much as she pretended about the monotony of dishwashing. In Interviews with Betty Friedan, Michele Kort writes:

As her career took off, her marriage ran aground. After the divorce, ending more than twenty tumultuous years, Carl Friedan blasted his ex in an interview, claiming she “never washed 100 dishes during twenty years of marriage” and that his new wife made chicken soup and shined his shoes. [Betty] Friedan laughed and replied, “All I can say is, to each her own. I’m so mechanically inept, I can barely shine my own shoes.”

This makes perfect sense if the issue isn’t really doing dishes, but rather what they symbolically represent. Friedan, like many women of her time, felt she was being “imprisoned” in the home. Hence, she wrote extensively of “trapped housewife syndrome.” She believed careerism was the way to escape. Doing dishes was one of the many links that kept her metaphorically chained to the household. Therefore, to toss off the burden of dishes was to be freed from the drudgery of the home—to seek self-actualization in a career.

Obviously, this flies in the face of Scripture. In Proverbs, God speaks of a wicked wife as one who “is boisterous and rebellious; her feet do not remain at home” (7:11). The contrast to the godly wife could not be more stark: one builds her house, while the other tears it down with her own hands (14:1). This is why Paul not only exhorts young women to love their husbands and children, but to also be “workers at home” (Titus 2:4).

But what about the Proverbs 31 woman? Isn’t she a careerist who has escaped the household? Only in the warped minds of feminists. She is, in fact, a diligent wife who has expanded the boundaries and influence of her household. Her husband’s heart trusts her, and she smiles at the future (vv. 11, 25). Careerism was not an option for women in the ancient Near East, unless you count whoring and witchcraft. The reason for this is not patriarchal oppression, but pre-industrialism—as we’ll cover very shortly.

Scripture unambiguously commends the work of the home, and calls women to joyfully give themselves to it.

And yet we have the constant call from pastors and female “theologians” for men to do some dishes.

Take for example Aimee Byrd. Back when she was still closeted and pretending to be orthodox, she wrote an article on Mortification of Spin—evidently a precursor to her later book of the same name: Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. (Note the preposition: recovering from it.) The post is mostly a meandering rant against John Piper for saying, “The more women can arouse men by doing typically masculine things, the less they can count on receiving from men a sensitivity to typically feminine needs.” Admittedly, Piper’s wording in the larger section she quotes is awkward—but what is notable is the conclusion of Byrd’s post. She rejects housework as tied up with femininity, and advances instead the myth of choreplay:

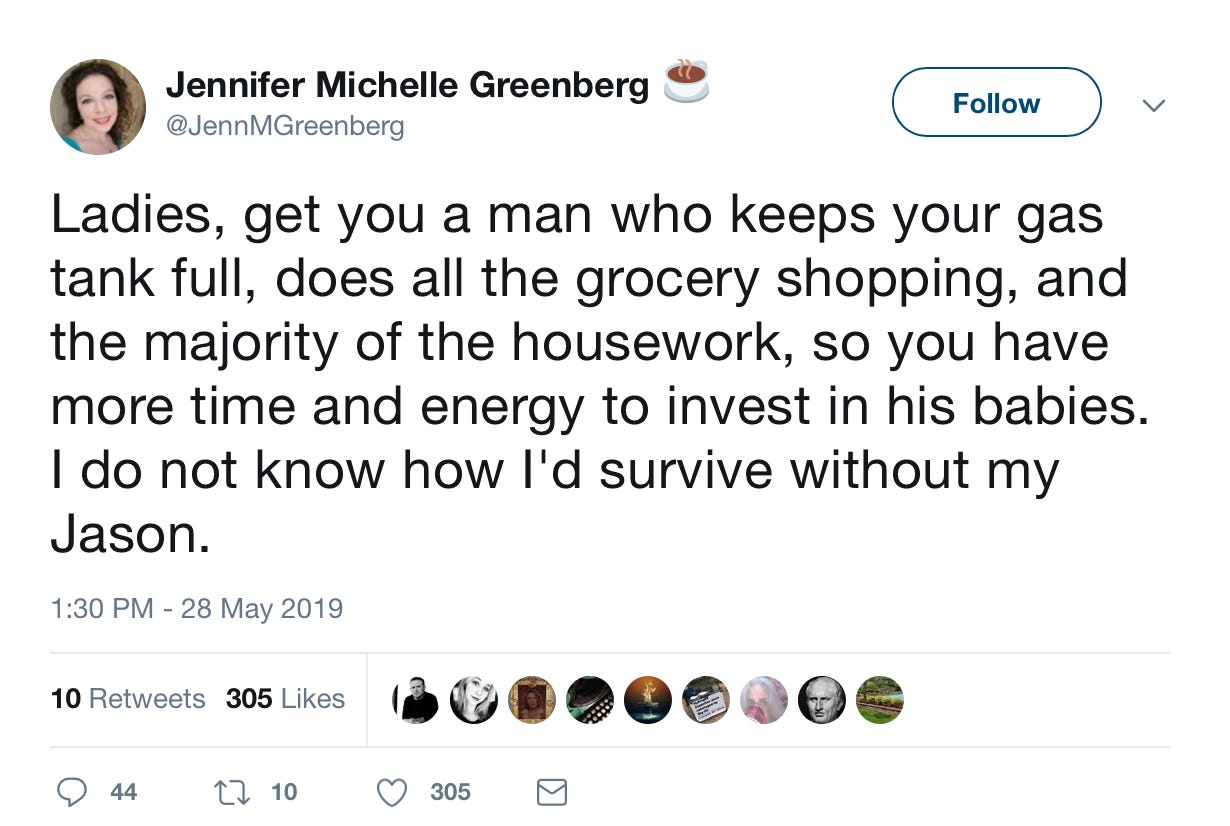

Byrd isn’t an outlier. There are many others like her. For example, we have so-called complementarian Christian musicians taking it beyond dishes:

Byrd and Greenberg, like Friedan before her, desire to be freed from the burden of washing dishes—and from everything else they represent. Their greatest “feminine need” is to be unshackled from the monotony of housework.

What’s the solution to this problem?

Is there even a problem?

Yeah, there is a problem. Big time. But it’s not with working in the home.

The problem is that most pastors—and maybe especially complementarians—share Friedan’s feminist view of the household. This is the subtext of their constant calls from the pulpit for husbands to do dishes, laundry, sweeping up. It’s as if they think that the work of the home is especially cursed.

This is compounded by how supposedly blessed the alternative is. A woman must “sacrifice” an exciting career…for the menial slavery of the home.

This being so, the best way a husband can love such a wife is to bear her “sacrificial burden” by doing some dishes, and so forth. It’s the least he can do, seeing how he is out there living the soul-satisfying life of a careerist while she labors in miserable futility. She could’ve been an astronaut, you know.

The problem is the church peddling a feminist view of the household. The problem is pastors telling men to step up to implement a fake solution to a fake problem. Although a husband “chipping in” can bring momentary relief to household discontent, the real issue runs much deeper than most white knight pulpiteers are willing to admit.

It runs deep into something built into the foundation of the world—something we have almost forgotten exists.

God’s design for households

The household is not an afterthought in God’s design for human society and productivity. It is central. When God created mankind, he gave them a mandate to be fruitful, multiply, fill the earth, subdue it. And they were to achieve this through the household.

But before we explain this, we need to remind ourselves about how the fall complicates the creation mandate. In The Story of Sex in Scripture, William Mouser explains:

In addition to the sentence of death, God curses the work of man and woman, that is, the productivity of their specific domains. Since Adam comes from the ground to work the ground, God curses the ground. It will be unproductive; labor will be hard. His own body will sweat as he struggles to make a living from a rebellious earth even as he journeys towards death, to return to the dust from which he was made.

Woman is not made directly from the earth or for the earth. She is made from the man and for the man—for people. The curse affects her relationships in the family. First, her unique and central area of productivity—childbearing—is cursed with all sorts of pain and difficulty. Second, her created ability and desire to help her husband is cursed with a contradictory desire to rule him rather than to help him.

The curse creates quite the dilemma. By nature, each sex is driven to be fruitful in a way particular to their unique design. But the pursuit of that productivity always comes with the sting of the curse. Men want to cultivate a field—but that requires the hard work of overcoming thorns. Women want to cultivate a family—but that requires submission to a man, and the pain of bearing children. Thus, the curse functions as an abiding chastisement to lead us to repentance. As we struggle to do what we are made to do, we are reminded that we live in a creation desperately in need of redemption.

What does this have to do with washing dishes?

The reality is that doing the dishes stings more for a woman than for a man. Given how our society is structured, dishes are in her natural domain—homemaking. The housework seems more cursed to her because the curse itself cascades down to every part of the work of cultivating a family for which she was made. Just as men shirk their cursed work of provision, through porn and video games, so women shirk their cursed work of homemaking, through careerism and complaining till their husbands do it.

This brings us back to the household, because our society has vastly amplified these elements of the curse by gutting the household of its natural worth and desirability. The curse makes things futile and painful at the best of times—but in the modern day, work in the home is not just futile and painful because of the curse, but because of how we have stripped the home of its natural function, and thus its natural appeal.

Before the industrial revolution—across all history and all cultures—the home was inseparable from the household. This is why the Hebrew word beth means both a physical structure and a familial society. The house was synonymous with culture’s central and most fundamental unit of production and identity: men and women worked alongside each other to produce what they needed to live, and as they did so they also came to know who they were and what their place was in the world. The whole family was naturally bound by this work into a basic society, a whole body, in which each member participated for the greater good, and in turn found their principal meaning.

This creational household, the household as God made it to be, is existential. The existence of every member at the deepest level is constituted in their house before all else, just as the existence of every part of a body is constituted in that body.

Division of labor…and households

In the basic society of the household, husband and wife both worked according to their natural abilities. The men did heavier labor, occurring mostly outside the home; the women worked closer to the home and cared for the children. But both sexes labored much harder than we do today, because their work and cooperation was essential to their continued production and onetogetherness—and thus to their survival.

The industrial revolution plowed into this creational model like a steam train (we use the analogy advisedly). Within a generation or two, production was separated from the home—consolidated and homogenized in factories.

At first, entire families commuted to these factories to work—naturally, for what else would you do when the household itself is for production? If the place of production moves, the whole household moves with it. But it takes very little time for mindsets to change. As we’ve noted, the creational model is that the home is inseparable from the household. The natural place of the household is the house. So when you do move the location of production elsewhere, you in principle separate the household from useful work—even if it takes a little while for the households themselves to catch up.

But catch up they did. In Orthodoxy, G.K. Chesterton famously wrote that:

Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.

Except, when those who merely happen to be walking about have been sufficiently separated from those who came before—as they will be when you break up their very households—they lose their onetogetherness with them. And with that, they lose any sense of obligation to their practices. When one’s identity is no longer constituted in a body that exists across time, traditions become alien things to be cast off. Young men, especially, as they were dislocated from the names and ways of their fathers, sought to make their own names and ways instead. Rather than seeking to ground their identities in honoring their fathers, they ended up grounding their identities by eschewing their fathers.

This is not to say that young men never rebelled against the ways of their parents before the industrial revolution. Jesus tells the story of the prodigal son. But the modern idea of the “rebellious teenager” is certainly, in large part, a production of the modern, eviscerated household.

It’s not only teenagers that suffered, of course. By relocating production, the industrial revolution broke apart households completely—and thus ensured the casting off of much of the traditional, natural, creational onetogetherness that had previously characterized them. A family going to work in a factory rapidly evolved into the man “going to work” and the woman “staying at home.” Thus the very atom of the household—the marriage—was split.

It is hard for us to fathom how desperately this affected women. Their previous place in producing and providing for their homes was obliterated almost overnight:

It is a formidable list of jobs: the whole of the spinning industry, the whole of the dyeing industry, the whole of the weaving industry. The whole catering industry and—which would not please Lady Astor, perhaps—the whole of the nation’s brewing and distilling. All the preserving, pickling and bottling industry, all the bacon-curing. And (since in those days a man was often absent from home for months together on war or business) a very large share in the management of landed estates. Here are the women’s jobs—and what has become of them? They are all being handled by men. It is all very well to say that woman’s place is the home—but modern civilisation has taken all these pleasant and profitable activities out of the home, where the women looked after them, and handed them over to big industry, to be directed and organised by men at the head of large factories. Even the dairy-maid in her simple bonnet has gone, to be replaced by a male mechanic in charge of a mechanical milking plant. (Dorothy L. Sayers, Are Women Human?)

Enter the 1950s housewife

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out the long-term societal effects of this atom-splitting. Households became increasingly less productive, and increasingly less existentially important. A vicious cycle was set up, to such an extent that the mere survival of households today is a testament to how deeply scored the pattern is into creation. But we have lost the existential household—even the very idea of it. We have lost nearly all of what was once considered the basic body in which all members share a foundational identity in productive pursuit of mutual wellbeing. We have replaced it with a sentimental household: less a society or a body, than a location where blood-relatives gather to sleep and have their emotional needs met.

We have swapped a deep shared identity established through production, for a shallow shared experience established through consumption.

This gets us back onto our central question. There is much we could say here about the household itself, but we are focusing very tightly—and the issue of consumption versus production, experience versus identity, is central to the question of who does the dishes.

In a modern household, the members all consume—often each other—starting with the marriage itself which arises from nothing but romantic feelings. A modern household is unlikely to survive more than one generation—because everything it needs is actually outside itself. Food comes from the supermarket; money comes from the workplace; entertainment comes from the internet…as does social “fulfillment.”

Because of this, the modern house is a place where many women would not want to stay all day. Children themselves are a liability rather than an asset—they cost a great deal, but contribute nothing to the house except the ephemeral benefit of emotional fulfillment. Lest you think we are mocking the emotionally fulfilling nature of children, understand this: emotional fulfillment itself only happens when you’re doing something together that matters. The thing God designed mothers, fathers, and children to find emotionally fulfilling is building a house. But modern mothers don’t build houses. Their emotional fulfillment has to come from “quality time,” which basically means time doing something fun together—because all the other time is taken up, either by someone else doing the work of mothering and fathering for them, or they themselves doing the work of building a house for someone else. (Not even a real house—a corporation.)

Since so much of the work that matters happens now outside the home, it is not surprising that a woman feels trapped inside the home. She feels like a servant left behind to look after her husband’s lodgings while he does the productive work they were both made for. She feels like a nanny left behind to entertain her husband’s children, while he gets to feel useful and recognized by others.

Her work feels menial and inessential because it is. It is not fulfilling the purpose for which she was made, and so in a significant sense it doesn’t matter. The picture of the 1950s housewife bored to death and swimming in meaninglessness may be exaggerated, but it is not altogether false. The household has gone from being a strong, weighty thing to a weak, wispy one—and that was true by 1950.

Hence, the house is now a place from which to escape to more glorious things. A place that smothers identity, rather than creating it. A source of death by consumption rather than life by production. Life is happening out there with the men. Who wants to be cooped up at home?

This doesn’t mean that feminism is right. The feminist mindset has existed since long before the industrial revolution in the form of foolish, brassy women who will not stay at home, who tear down their houses with their own hands. But it does mean that in this case, feminists can have a point.

So…who does the dishes?

If it isn’t obvious by now, our answer is: you’re asking the wrong question.

This answer should be every pastor’s response.

Stop asking questions that presuppose an emaciated, unbiblical household, and start asking how to build a healthy, God-glorifying one. What is the use of complaining about the dishes, or demanding that men step up to do their fair share, when the house itself is broken down and crumbling? Stop trying to ameliorate the feminists’ point by making out like it’s not so bad provided the man just does more. Instead, concede that there is a real problem, and recognize that trying to fix it by properly dividing the housework is like trying to keep Titanic afloat by speeding up and correcting course after being slowed down by that iceberg.

If you are a pastor, we implore you to stop pouring concrete into the mold of the unbiblical sentimental household, by telling men to step up. No man should be above doing housework, but demanding he do it is just preserving a century of heteropraxy. You should rather be preaching the glorious doctrine of the natural household itself; the existential beth in which men, women, and children all find shalom: satisfaction and meaning, life and purpose, inclusion and ownership, wholeness and completion, as they work together for the glory of God.

That is the only thing that can resolve the feelings of alienation that drive the contention around housework in the first place.

We are not advocating by any means for a return to preindustrialism. Even in cases where households can become productive through traditional occupations like farming or smithing, technology is here to stay; you cannot compete without it, and neither should any sane person want to. Rather, we are advocating for a return to production in the household rather than mere consumption; a return to self-consciously treating the house as a place of mission rather than a place of recreation; as an organ of dominion rather than an abstract institution of emotionalism.

We know this is easier said than done. We ourselves are only starting to work out how to reform our houses along these lines. What does mission look like? How do we become productive? How can we more closely involve our wives and children in our work? How can we effectively create and cast a vision for everyone to follow? These are questions we will have more to say on as we report back our own efforts.

Until then, be watchful for deeply-entrenched practices that are reinforcing an unbiblical doctrine of household. Stand firm against scorn and ridicule for seeking to reform your house. Act like men and be strong, because strength is power, and power is work done over time, and work done over time is production. And let it all be done in love, because love is onetogetherness—the foundation and purpose of a meaningful house.

Further thinking

The issue of sentimental versus existential households also has huge implications for the church, which is after all the “household of God” (Ephesians 2:9). If you come to the church with a sentimental concept in view, how will that affect your understanding of what it is, what it should do, and what your place in it is? Indeed, given that a qualification for a pastor/elder is to rule his own house well, can we even say that modern pastors are biblically qualified when they are not ruling biblical households?

Further reading

Rory Groves, Durable Trades: Family-Centered Economies That Have Stood the Test of Time (book)

Alastair Roberts, A Biblical Theology of the Household (video or text).

C.R. Wiley, Man of the House: Recovering a Christian Vision for the Family (book)

G.K. Chesterton, The Drift from Domesticity (essay).

Alastair Roberts, The Church and the Natural Family (video or text).

And of course, check out our own book, It’s Good To Be A Man: A Handbook for Godly Masculinity.

OK. So you've identified that the problem is much larger than the question of "Who Does the Dishes" and that we should strive for a biblically ordered household. In the meantime, dishes pile up in the sink. Husbands either follow the advice of the white knights and concede to their wives' demands, or they prefer to focus on more manly duties, while the wives fester a resentment against all things patriarchy. So if "Who Does the Dishes?" is the wrong question to ask, maybe the better question is, "What are the practical steps necessary to take us from where we are now to the ideal goal of a biblically ordered household? And how does a man desiring such an outcome faithfully and effectively lead his family in that direction?"